The Coso region, located within the Naval Air Weapons Station (NAWS) China Lake,

in the desert of interior southern California, is home to some of the most

spectacular displays of Native American rock art anywhere on the continent.

The Coso region, located within the Naval Air Weapons Station (NAWS) China Lake,

in the desert of interior southern California, is home to some of the most

spectacular displays of Native American rock art anywhere on the continent.

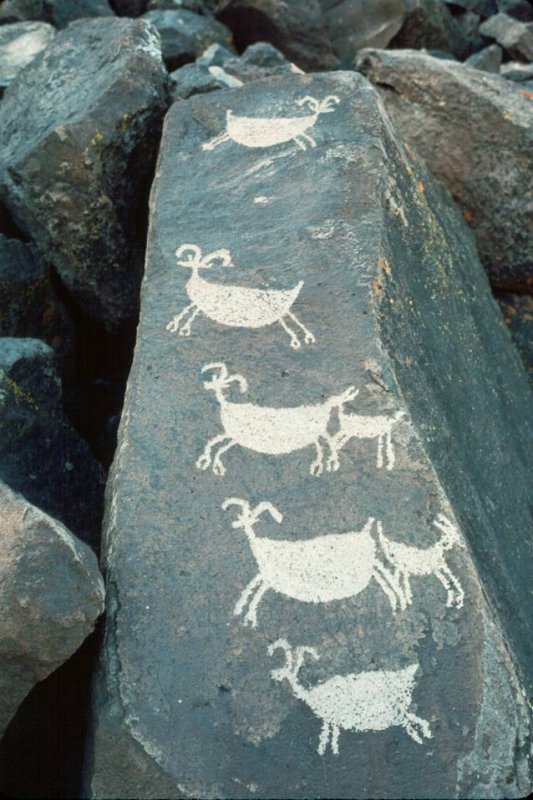

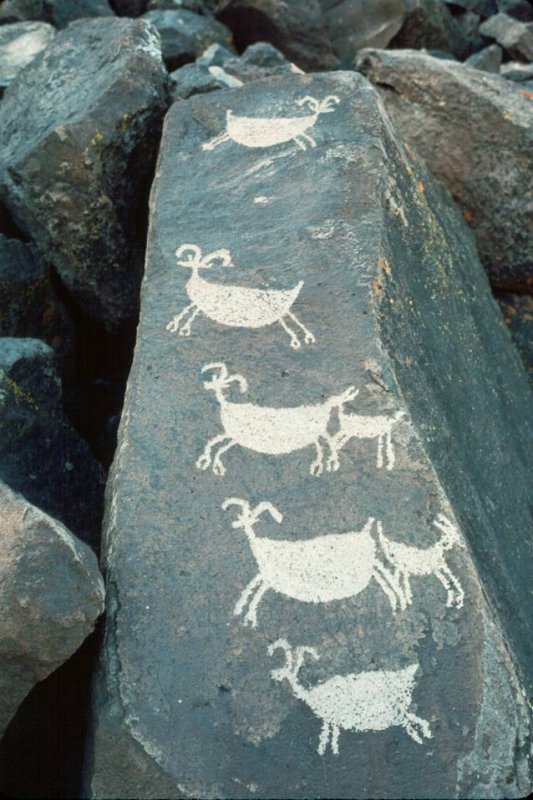

Distinctive, highly stylized images of bighorn sheep, shield-like images, and

human-like figures distinguish Coso rock art from that of surrounding regions.

Most of these figures were made by pecking, grinding, or scratching a design

into a rock's surface. Researchers refer to these types of designs as

petroglyphs, as distinct from painted ones (pictographs).

Most of the Coso petroglyphs appear to be 1000 to 3000 years old, though the

practice of making rock art in this area may have begun with the earliest

occupation of the region (as early as 13,500 years ago) and continued into

historic times.

Here, you can see examples of this rock art at several recently discovered

sites at NAWS China Lake, along with commentary on the rock art, as well as maps

and other information about the sites.

RESPECT AND PROTECT

Rock art provides a window into the past rituals, beliefs, and artistic abilities

of its creators. Because of its scientific, aesthetic, and religious significance,

it deserves respectful behavior. This unique and ancient artwork is also very

fragile. We can help ensure its preservation so that our grandchildren's

grandchildren will also be able to appreciate it. Please never touch or apply

any chalk or other material on the designs. Please avoid walking or sitting on

rock art panels. When visiting a rock art site, leave no trace of your trip so

that others may have the pleasure of finding the site in its pristine, undisturbed

condition. If you see vandalism or damage occurring on public land, please report

it to an appropriate land steward.

WHAT DOES IT MEAN?

Rock art can be difficult for researchers to interpret. Many rock art traditions

have few or no living practitioners. In the absence of direct explanations provided

by the artists, attempts to find meaning in rock art can be highly speculative.

Many different functions have been attributed to rock art. In some contexts, it

may serve as illustrative art that teaches a lesson or commemorates a noteworthy event.

In others, it may play a part in religious practices that seek

supernatural influence or control over events. In still other contexts, it

may mark territorial boundaries, or help to keep track of the passing of time

by marking celestial events such as equinoxes or solstices.

Two major theories on the function of Coso rock art have been proposed. One

theory connects it with so-called "hunting magic." Noting the immense number

of sheep drawings in the Coso engravings, Campbell Grant and others hypothesized

in the 1960s that the hunter-gatherers living in this area were heavily dependent

on bighorn sheep for subsistence, and that the rock drawings were created as part

of a ritual meant to ensure a successful hunt. The introduction of the bow and

arrow 1500 years ago led to more efficient hunting of the sheep, and hence eventual

depletion of their populations. As herds dwindled, the production of rock art --

particularly bighorn and anthropomorphic (human-like) designs -- intensified in

attempt to restore the sheep. With the final collapse of the sheep population,

the hunting magic was abandoned.

The other theory interprets Coso rock art as the work of shamans or medicine men

who drew natural symbols (mostly abstract geometric images brought to the mind's

eye when in a trance), images of the animal spirit helper that assisted the

shaman in obtaining supernatural power, or images of the shaman's transformation

into that spirit. Native American groups in the Great Basin commonly associate

rain shamans with bighorn sheep. The prevalence of bighorn sheep in Coso rock

art is interpreted as an indication that the area is particularly vested with

supernatural power capable of controlling weather. This theory has been developed

primarily by David Whitley, who has applied this interpretive framework to a wide

range of sites throughout the Great Basin.

The other theory interprets Coso rock art as the work of shamans or medicine men

who drew natural symbols (mostly abstract geometric images brought to the mind's

eye when in a trance), images of the animal spirit helper that assisted the

shaman in obtaining supernatural power, or images of the shaman's transformation

into that spirit. Native American groups in the Great Basin commonly associate

rain shamans with bighorn sheep. The prevalence of bighorn sheep in Coso rock

art is interpreted as an indication that the area is particularly vested with

supernatural power capable of controlling weather. This theory has been developed

primarily by David Whitley, who has applied this interpretive framework to a wide

range of sites throughout the Great Basin.

Grant's theory suggests a chronological sequence in which abstract forms come

earliest, followed by the representational designs of the hunting ritual. Other

rock art studies indicate that these representational designs were followed by

simple, scratched designs. In contrast, Whitley's theory would indicate that all of

these different styles were produced more or less continuously. Thus, deciding

between these competing theories would be easy if Coso rock art could be dated.

Unfortunately, this is a difficult task. Petroglyphs cannot be directly dated

like other archaeological finds, and archaeologists must rely on other lines of

evidence. Superposition, that is the placement of one rock art element over

another, indicates the relative age of those two elements. Observing many such

superpositions may allow the researcher to determine that a particular style of

rock art is older than another, but it does not fix the absolute age of either.

Also, different figures of a rock art panel may simply look more weathered than

other elements, suggesting that they have been exposed to the elements for a

longer time. As with superposition, it takes a large number of these kinds of

observations to show trends through time in rock art styles.

Another way of determining the age of rock art is to date nearby archaeological

finds, such as the remains of dwellings, hearths, or flaked stone artifacts

such as arrowheads. While it cannot be proved beyond any doubt that the rock

art and the nearby finds at a given archaeological site were actually produced

at the same time, archaeologists can look at many such archaeological

"associations" and discern trends that make the overall picture much more

convincing than would any single archaeological site.

WHAT DOES IT LOOK LIKE?

Coso rock art is found throughout the forested uplands of the Coso Range, as

well as the broad brush-covered plateau to the south. Although these areas

differ in many ways, they both have large outcrops of basalt that form

extensive scarps or rimrocks on which the rock art is typically found. These

outcrops have developed a dark brown-to-black patina or "desert varnish" that

is easily pecked or scratched away to reveal the lighter rock beneath.

Many different kinds of designs are found in Coso rock art. These include abstract

patterns such as grids, nested and bifurcated circles, "shields," patterns of

dots, and parallel and radiating lines. Representational figures make up another general

type, and are usually sheep, human-like figures, deer, mountain lions or dogs,

and rectangular "medicine bags" or purse-like figures. These types of designs were

usually made by pecking at the rock with a hammerstone. Another, very different

technique was to simply scratch the surface of the boulder. As discussed above, this simple

three-part scheme of abstract, representational, and scratched designs

is thought by some researchers to reflect stylistic changes over time.

Here you can see the rock art at six archaeological sites in the Coso region.

Two environmental settings are represented: the Basalt Lowlands and the

adjacent Pinyon Uplands.

Basalt Lowlands Sites

Rock art in the basalt lowlands is mostly representational, with fewer abstract

designs and almost no scratched designs. The panels are usually placed in

conspicuous locations, not hidden in cracks or between boulders. Individual

elements tend to be fairly simple designs, and are often less than 20 centimeters

(8 inches) in size.

Pinyon Uplands Sites

Rock art in the pinyon uplands consists mostly of abstract and scratched designs.

Representational elements are much less frequent. The pecked designs are typically

high-contrast, and often placed in a conspicuous location. Scratched designs,

however, tend to be difficult to see. This is because of the thin, shallow

scratch marks used and because they were often placed on light surfaces such

that there is little contrast with the rock's unmodified surface. They are

also fairly often in hidden or inconspicuous places, such as inside narrow

crevices and close to the ground surface.

WANT TO LEARN MORE?

There is public access to one canyon that contains an extraordinary

concentration of Coso rock art, through tours arranged by NAWS China Lake's

Public Affairs Office and by the Maturango Museum in Ridgecrest. To learn how

to arrange a tour, email peggy.shoaf@navy.mil,

or contact the Maturango Museum at (760)375-6900

(http://www.maturango.org).

Further Reading

Freers, Steven M., ed. (1999) American Indian Rock Art, Volume 25. American

Rock Art Research Association (ARARA), Deer Valley Rock Art Center, P.O. Box

41998, Phoenix, AZ 85080

Grant, Campbell, James Baird, and Ken Pringle (1968). Rock Drawings of the

Coso Range, Inyo County, California. Maturango Museum Publication No. 12.

Maturango Press, Ridgecrest, California.

Whitley, David S. (1996). A Guide to Rock Art Sites: Southern California and

Southern Nevada. Mountain Press Publishing Company, Missoula, Montana.

Whitley, David S. (2000). The Art of the Shaman: Rock Art of California.

University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

Younkin, Elva, ed. (1998). Coso Rock Art: A New Perspective. Maturango Museum

Publication No. 12. Maturango Press, Ridgecrest, California.

Prepared by Far Western Anthropological Research Group, Inc., 2727 Del Rio Place,

Suite A, Davis CA 95616

www.farwestern.com

Amy J. Gilreath (author and photographer), Jerome King (author) and

Reinhard Pribish (graphic designer)

|

The Coso region, located within the Naval Air Weapons Station (NAWS) China Lake,

in the desert of interior southern California, is home to some of the most

spectacular displays of Native American rock art anywhere on the continent.

The Coso region, located within the Naval Air Weapons Station (NAWS) China Lake,

in the desert of interior southern California, is home to some of the most

spectacular displays of Native American rock art anywhere on the continent.

The other theory interprets Coso rock art as the work of shamans or medicine men

who drew natural symbols (mostly abstract geometric images brought to the mind's

eye when in a trance), images of the animal spirit helper that assisted the

shaman in obtaining supernatural power, or images of the shaman's transformation

into that spirit. Native American groups in the Great Basin commonly associate

rain shamans with bighorn sheep. The prevalence of bighorn sheep in Coso rock

art is interpreted as an indication that the area is particularly vested with

supernatural power capable of controlling weather. This theory has been developed

primarily by David Whitley, who has applied this interpretive framework to a wide

range of sites throughout the Great Basin.

The other theory interprets Coso rock art as the work of shamans or medicine men

who drew natural symbols (mostly abstract geometric images brought to the mind's

eye when in a trance), images of the animal spirit helper that assisted the

shaman in obtaining supernatural power, or images of the shaman's transformation

into that spirit. Native American groups in the Great Basin commonly associate

rain shamans with bighorn sheep. The prevalence of bighorn sheep in Coso rock

art is interpreted as an indication that the area is particularly vested with

supernatural power capable of controlling weather. This theory has been developed

primarily by David Whitley, who has applied this interpretive framework to a wide

range of sites throughout the Great Basin.